Pests and pestilence — this is a theme that runs through most of the calls, emails, and visits to the Extension office.

The usual question is: “What do I spray to kill this?” Sometimes clients are hesitant to spray for pests. Sometimes, though, it seems like they are ready to prepare for all-out warfare.

Perhaps the right question to ask is not about what to spray but about how to prevent the problem in the first place, and to take the advice of Ben Franklin that “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” It’s a philosophy we call Integrated Pest Management. The secret is planning ahead, instead of waiting for problems to present themselves.

That’s why it’s important to think about it early in the garden season.

The premise of IPM is to use the best practices available to avoid a pest invasion, using a spray as the last resort. It aims to manage pests and diseases over the long term by managing the ecosystem and making it unfavorable to the pest. It is a great philosophy for all gardeners to use, but it is especially important for fruit and vegetable gardeners.

Reducing damage or loss of crops is key to having a productive garden. And many people hope to reduce or eliminate using pesticides on their crops. Using IPM is an important step for this.

This also goes hand-in-hand with the concept of a threshold, meaning there is a certain amount of damage that is tolerable before an action of control is taken — no need to declare chemical warfare on one or two potato bugs.

Whether you are talking fruits and vegetables or ornamental landscape plants, there are practices you can adopt to help avoid problems. The key is to be prepared and be proactive, rather than reactive when you have a problem.

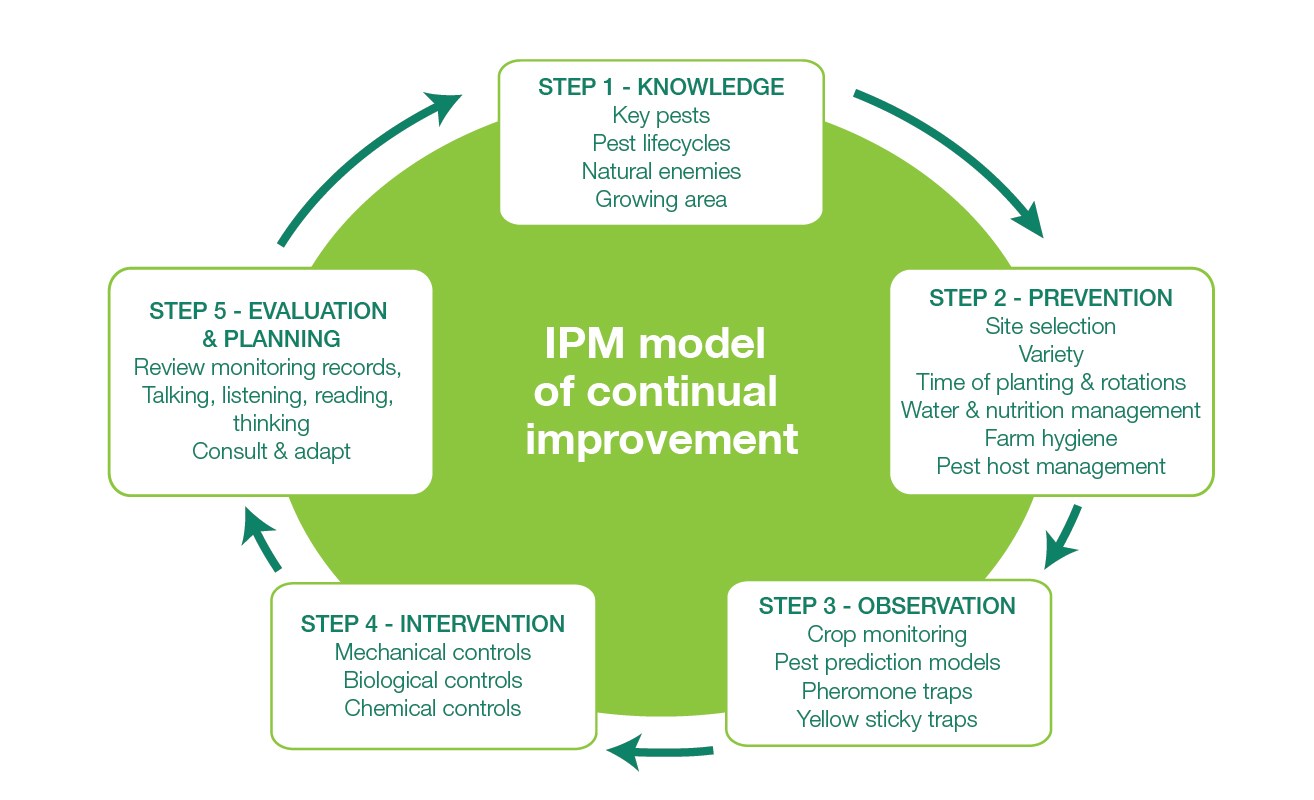

There are five steps to integrated pest management:

- Identify pests, their host plants, and any beneficial organisms.

- Establish monitoring guidelines for pests. Scout for pests and assessing damage.

- Evaluate pest damage and establish a threshold for damage.

- Implement control using biological, cultural, physical and chemical (as a last resort) means.

- Monitor, evaluate, and document results of management controls.

And then I’ll add:

6. Rinse and repeat, if necessary.

Management Approaches

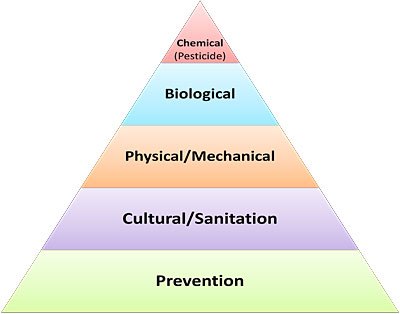

There are several different management approaches to controlling pests. These can be used individually or in combination to combat specific pests.

Image result for integrated pest management

Levels of IPM start with a base of prevention. IPM does not eliminate the use of chemical controls, but reserves them as the “last resort”. Photo: University of Nevada Cooperative Extension

Cultural controls are measures that reduce pest establishment, reproduction, survival or dispersal. Basically, it is to keep pests from reproducing or expanding.

Crop rotation is a good cultural control for reducing disease and insects in the vegetable garden. Keeping a crop in the same place year after year lets diseases and insects that affect that specific plant build up over time. For example, you want to move tomatoes to a new place every year and leave at least four years between plantings in each specific spot to reduce pests such as early and late blight.

Cultural control also includes cleaning tools between uses to limit spread of diseases, disinfecting wooden tomato stakes to limit spread of blight, and implementing good drainage to reduce root rots and diseases. There’s also a lot to be said for cleaning up the garden between seasons to remove debris where diseases and insects can overwinter.

Physical control includes killing a pest directly or making the environment unsuitable for their growth. There are several practices many gardeners already do that fall in this category. Using wood mulch to suppress weeds is common in the landscape, and many vegetable gardeners use straw, newspaper or landscape plastic mulch to suppress weeds, reduce soil-borne disease and warm the soil earlier. Using traps for rodents or for insects or picking off insects by hand are means of physical control. Removing diseased plant parts or even entire diseased plants can help reduce the spread of a disease to other parts of the plant or to other plants. Unfortunately, even with treatment it is often difficult or impossible to totally “cure” a plant of a disease after it has been infected – another reason that prevention is key.

One method I think many gardeners could utilize more is to install a physical barrier to keep pests from attacking plants. A row cover is an effective, chemical-free method to keep insects away from plants. You can use a specific row cover material you can find at garden centers, but you can also use thin, netlike material from the craft store like tulle (you can use leftovers to make yourself a tutu).

This is really easy to use on crops that don’t need pollinators, like leafy greens, cole crops and even beans. If you are growing something that needs a pollinator, like squash, you’ll want to remove the cloth when the plant starts blooming.

Biological control uses natural enemies — predators, parasites and pathogens — that affect your pest. Sometimes this means introducing or releasing the predator, like ladybugs to eat aphids, and sometimes it means making conditions favorable for these competitors and enemies.

Studies show that having diverse plant life increases beneficial insects that out-compete or eat your pests. So having a mix of plants in the garden and also incorporating an area of flowers in the garden can be beneficial.

Parisitized tomato hornworm – move him to a less desirable part of the plant and let him live. The parasitic wasps will hatch and infect more hornworms. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Parisitized tomato hornworm – move him to a less desirable part of the plant and let him live. The parasitic wasps will hatch and infect more hornworms. Photo: Wikimedia CommonsOther examples include using milky spore disease to control grubs in the lawn (which has been shown to have limited effect, and may require annual application) and allowing tomato hornworms that have been infected with parasitic wasps to stay in the garden so the parasites hatch out and kill more hornworms.

There are also some items available in the pesticide aisle that count as biological control, such as the use of Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) in products for chewing caterpillar-type pests such as cabbage worm. Such products are Dipel and Thuricide. There is now a bio-fungicide product on the market referred to as Serenade that helps prevent some foliar plant diseases. The product contains the bacteria Bacillus subtilis, which both acts as an antagonist toward pathogen (kills them or out competes them) and helps trigger an immune response in plants that helps them fight off pathogens. These bio-control methods are all labeled for use in organic production and are considered low-risk when use properly according to label instructions.

You can also say that the use of resistant cultivars to avoid diseases is an example of biological control. This applies both to landscape and food plants. If you have specific problems, look for plants that are resistant to those problems. There are rust-resistant daylilies, disease-resistant roses, blight-resistant tomatoes, and on and on.

Chemical control is the final option of integrated pest management if other means are not effective in controlling the pest. If you choose to use chemical control, the philosophy of IMP encourages the use of the least toxic chemical that provides effective control. Be sure to read all labels to make sure the product can be used on the plants in question, will control the issue you have, and that you know how to safely apply them. Following the label is the law – failure to do so could be breaking both state and federal laws that regulate pesticides.